This message is addressed to anyone curious about what comes next after the buzz that data creates (an explanation of this buzz can be found in the Harvard Business Review). Let’s not compare this buzz with a bubble such as the real estate bubble. Data can certainly be a capital asset, but its lifespan is infinite, and it is, above all, immaterial. How to link this to information assets?

In this article, we will look at this awareness, which dates back a few years to the birth of Big Data, but which will still be recent for most employees in any company that is not immersed in this multi-billion dollar niche.

We are therefore interested in an ecosystem that supports the digital transformation of a company.

We will describe this ecosystem through the prism of responsibility for data and the concept of Data Democracy, with the complexity of data through its transversal and systemic aspect, and with a data community that represents the beauty of collective intelligence.

If everyone is responsible, then no one is

In a democracy, everyone is responsible. In a company, this principle excels since a contract always binds an employee to his or her employer. In our case, would this mean that every employee in an organisation would become responsible for their data?

The issue is not so trivial. Responsibility is a complex subject in business, even more so in 2020, as responsibilities become mixed and intertwined with the reorganisations, managerial innovations and agile transformations that follow.

‘Why would the expertise exist if no one really “owns” the data? Business will be data users but the pseudo ownership will fall onto IT in the absence of anyone else.’

The Chief Data Officer Playbook, pages 42-43. Caroline Carruthers and Peter Jackson.

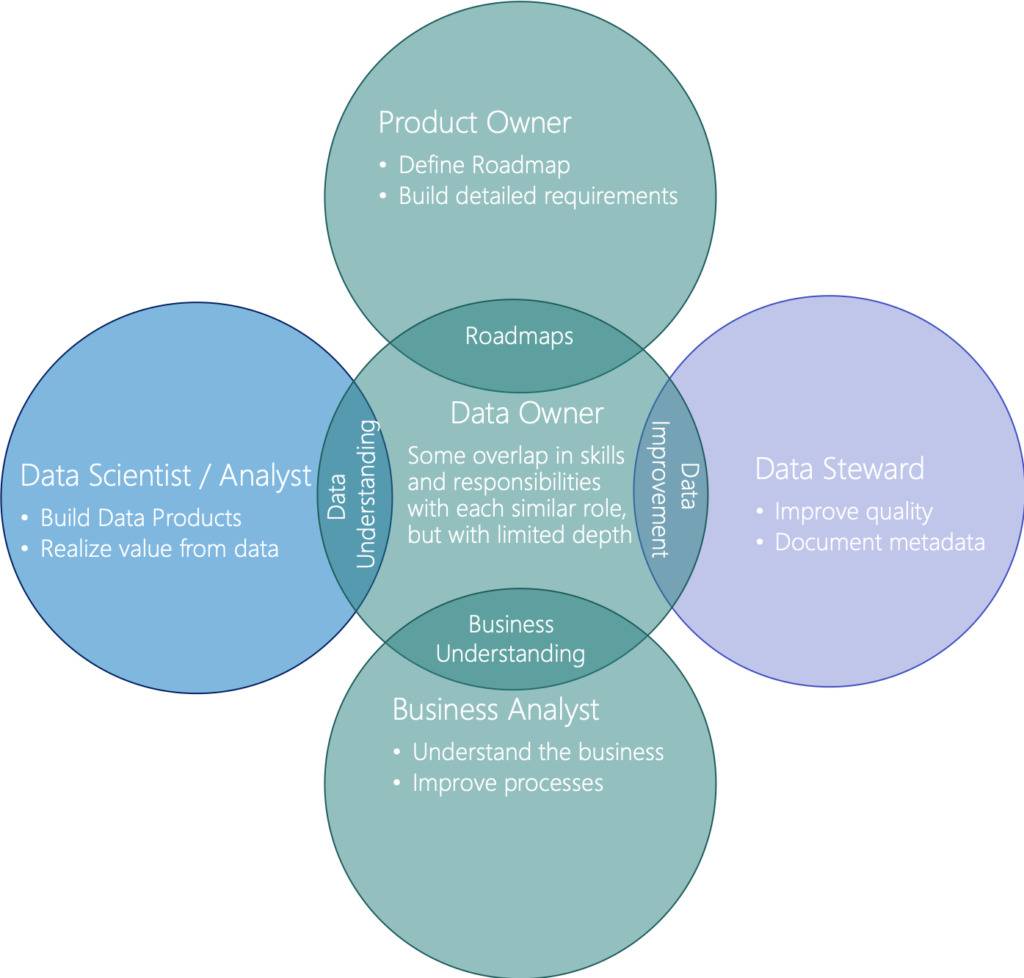

In the face of a responsibility, a role often appears. And more and more employees, because of their skills and commitment, are taking on several roles. This is easy for an organisation that does not change its structure, but difficult for employees who accumulate them, as part of their best efforts, and no longer have the capacity to do everything well.

Organisations are now required to become resilient, and hybrid in their methods. This is why, in their digital transformation, some companies are stopping this bad practice of combining roles, and creating functions or positions with the managerial lines, for a new organisation that wants to be data-centric, in addition to being business-centric and customer-centric, etc.

A resilient, hybrid and agile organisation therefore easily accommodates new roles, but more importantly new functions and new jobs.

In this way, responsibility for data is simply a matter of culture and strategy. Data ownership or data stewardship can be deployed in the business lines that bear their challenges and risks. In a concrete, operational and efficient but transversal way, this new data community made up of Data Stewards, Data Owners and Data Champions, among others, participate in the democratisation of access to information in their organisation.

It is therefore the organisation that must accompany the structuring of data governance functions, so as not to lead to a concentration of roles on the same people.

Even if this type of organisation removes some of the complexity in the deployment of data governance, the data itself carries a certain complexity that the organisation must calmly accept.

Information assets: data is a systemic object

Cross-cutting issues are systemic issues. Effective, efficient data governance in an ecosystem is a cross-cutting issue, so it is systemic. More precisely, with data, if we go to the end of the issues, we reveal more and more limits, impacts and constraints that escape the operational staff and sponsors.

For example, whatever the industry, when a business line decides to market a new product or service, it is first set up for customer-centric uses: marketing, sales, and logistics.

So here we already have three big players who will have a particular way of describing a product. Once this product is sold, it will interest finance, accounting and treasury.

If these actors are not integrated at the design stage of a product, there is a good chance that the technical accounting will not be aligned with the following transactions… So the product sells, but the money does not come in.

And this is just one example, imagine all that happens in a day in a CAC 40 company. A systemic approach makes it possible to model all the causes and consequences to anticipate certain risks.

Governing the data means taking on the challenges of a company while controlling the risks.

‘To explain and understand the situation, many elements must be taken into account (general situation, specific context, strategy of the actors, etc.), a systemic analysis must be carried out objectively and rigorously, and the information gathered must be well controlled and compared.’

To get from Big Data to solutions, you have to be able to identify the problems. Michel Bruley, 15 September 2019 on decideo.fr.

Go fast, go faster. It is becoming increasingly difficult to take the time to do things right in large organisations. In fact, countries such as France are experiencing a new decentralisation with the explosion of independence, startups, French tech, etc.

This is a risk that is still underestimated in companies: the flight of their ‘brains’ to independence, to the startup, because these environments are a priori full of meaning. The pure development of ideas can be found here. So what does this have to do with data?

The paradigm shifts that organisations are undergoing in their digital transformation and the arrival of new ‘tech’ or ‘digital native’ talent create interesting phenomena to observe in the difficulties, or even chaos, that the differences in culture create, depending on the size of the organisation and the careers in the data or digital sectors. But that is not the focus of this article.

It is generally rather easy to interest and motivate employees in the initial phases of projects. But in the medium and long term, if there is not a system in place, careers fade away. However, the exercise is not easier for an employee who changes company for these reasons, as the destination will not necessarily have a system in place. And the cultural pitfall is all the greater because these digital natives do not operate at scale: either because their objectives are focused on a product, or because of their very vertical positioning within an organisation.

When an organisation implements the use of systemics in cross-functional projects and strategic programmes, it can put itself in a position to master the human issues as well: experience, meaning, fulfilment, profit-sharing, learning, empowerment, etc. These human issues will perpetuate knowledge within the company and guarantee digital transformation.

The intelligence of a collective

Employees can often also find themselves in a silo effect. Silos in companies are more or less porous. Data governance paradoxically incorporates many levers to cross these silos. Why? Because in this 4th industrial revolution, artificial intelligence and innovation go far beyond the borders of a company. Employees are also consumers.

These information assets are now in the hands of a new player in a data community: the CDO. Organisations have high expectations of CDOs.

‘A trap that lots of organisations fall into is that the Chief Data Officer and their valiant team are now responsible for all their data problems.’ The Chief Data Officer Playbook, page 61. Caroline Carruthers and Peter Jackson.

How to grasp the levers for deploying data management at scale? Many agree on a use-case approach. Yes, the principle is correct. But what use-cases?

The complexity of data has been highlighted by its systemic and transversal nature. So which use-cases could allow you to take into account this systemic and transversal nature while simplifying the problem and facilitating cooperation and collaboration?

- First of all, stop talking about ‘data’, and take an interest in your company’s business cases. The most trivial are often the most critical.

- First, work on the eligibility criteria for a use-case: for example, the number of different tasks, the number of users, the number of different applications, the number of different data sources, the turnover generated, etc.

- Then find use cases with your employees, so that you can immediately focus on transparency and participation.

- Use large, beautiful materials to formalise them (brown paper for example).

- Naturally, magically, the use-cases data will appear.

Because you were first interested in the real, concrete problems for and with your data community.

And then, if you like democracy, as all problems are important, but it is not yet time to solve them, choose the vote to select the use-cases that will accompany you throughout the governance of your information assets.

So the less we talk about Data, the more it becomes just a pretext, and the more we leverage cooperation and collaboration to drive the digital transformation of a business.

In another article, we discuss more precisely what Data Democracy means, through the culture of a company and the different cultures of its employees.